Opening up Capital Markets to Supply Chain Finance

Opening up Capital Markets to Supply Chain Finance

Supply chain finance is traditionally a banker’s game. An anchor is traditionally assessed by looking at its track record and working on setting up a programme that undertakes a painstaking methodical, name-by-name KYC and credit assessment. This old artisanal approach to credit—setting limits based on the look-and-feel and the personal touch—seems to be stuck in a dead-end. Even in the largest companies, well over half of their suppliers and dealers are too small to make the bankers’ cut. Is there a way to break free from and industrialise this process? This article considers the challenges and possible solutions for the same.

Twin Engines of Growth

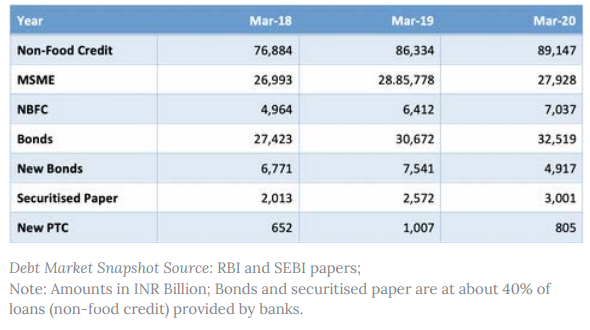

That India has one of the highest savings rates is well known. Less well known is the fact that mutual funds inflows over the last decade have easily outpaced the growth in bank deposits. Where has all that money gone? Granted that a significant part goes into the share market, but a big chunk also finds its way into the capital and money markets, driving the growth in bonds and securitised instruments.

Over the last few years, however, the credit crisis has choked banks. Where does one go if the banks will not or cannot lend you money in India? To the capital markets? Money markets? Foreign portfolio investors? In fact, corporate India has been doing the rounds with all of the above. But to go to these places, one needs a passport called ‘Rating’. Rating charts, meanwhile, show that only a small proportion of companies (<1,000) have AA’ or higher ratings and they corner a very substantial majority of the funds available to the corporate bond and money markets. So if just a few hundred companies make the cut in terms of rating, how do small businesses drink from this ocean of liquidity?

Vaman to Vikram in Three Steps: School It, Cool It and Pool It!

- Capital markets have long figured out a statistical solution to credit. First find a model that works, where lenders are schooled to fund viable businesses and document the process

- Once this is done for a while and the portfolio is seasoned (with a cooling period in between), one may proceed to step three

- Pooling borrowers. Statistics would forecast a default ratio. The pooled cash flows are tranched, i.e., a pecking order is created for who takes the losses from defaults first, second and last. These are the equity, subordinate and senior tranches.

The basic premise is that if there are a 100 borrowers, not all 100 will default at the same time. In fact, a fairly big percentage will repay if they are picked with the right profiles and credit history. The first two tranches—equity and subordinate—are set in such a way as to absorb losses even in extremely difficult environments The senior-most tranches can be rated ‘AAA’ or ‘AA’, or some combination where return expectations and risk appetites meet. The small borrowers who would individually be rated ‘B’ now stand tall as a collective ‘AAA’. It is a testament to sound statistics and economics that not one of the ‘AAA’ rated pools of commercial vehicle loans had defaulted in the last 15 years prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. Over the last few years, several new assets classes have been securitised—microfinance loans, mortgage loans and of late, even gold loans—but not supply chain as yet. The times, in fact, may finally be right for an asset class, which more than many others peculiarly fits the theoretical premises.

Supply Chain as an Asset Class

Traditional supply chain finance is an unsecured loan to dealers and vendors of large companies (or ‘anchor’). There is no direct recourse to the anchor, but there is a promise that the anchor will act in good faith—that it will refer borrowers with a track record of good performance and hold the threat over their heads that default to the lender would mean dismissal from the vendor or dealer network. In industries with a strong reliance on the anchor due to branding or technology, or where there is an oligopoly, this premise of ‘stop supply’ has proven surprisingly effective. Loans to vendors and dealers have low default rates in comparison to borrowers of similar size and financial metrics. So why are these assets not securitised, when they have all the key ingredients—a market hungry for funding, good credit histories and large volumes?

Operational Nitty-gritties

Dealers and vendors may be small, but their needs for finance mimic that of their anchors; they need to buy or sell almost daily. So the need for funds is in tiny trickle —even suppliers to billion dollar corporates would have drawdowns of a few lakhs or even a few thousand rupees—repayments are made on an invoice-by-invoice basis on staggered dates. This frequent drawdown and repayment would mean that a one-shot disbursement of a INR 1 billion (a minimum economic size for capital markets) is not on the cards. Plus once sold into a securitisation vehicle, all those tiny repayments have to be tracked. The next challenge, however, is about what happens when the money is repaid. Traditionally, the credit periods in supply chain finance is 90 days, giving the portfolio an average tenor of 45 days, which is too short a tenor for any serious provider of capital. This and other considerations have held back any serious attempt to bring this asset class to the capital markets.

Covered Debt

In the summer of 2018, a small finance company wanted to buy a supply chain business. Given its small size and consequent high cost of funds, it looked like the high yielding loan book to dealers was probably the best bet. A large pool of suppliers to a ‘AAA’ rated anchor was on offer, but it was priced too low to make any economic sense. Out of that sense of frustration was born the ‘Covered Commercial’ paper. To all intents and purposes, this was a regular commercial paper—it carried the advantages of any such market instrument easily divisible and easily transferable. But with the issuer’s rating at ‘A2’, it would never have been subscribed.

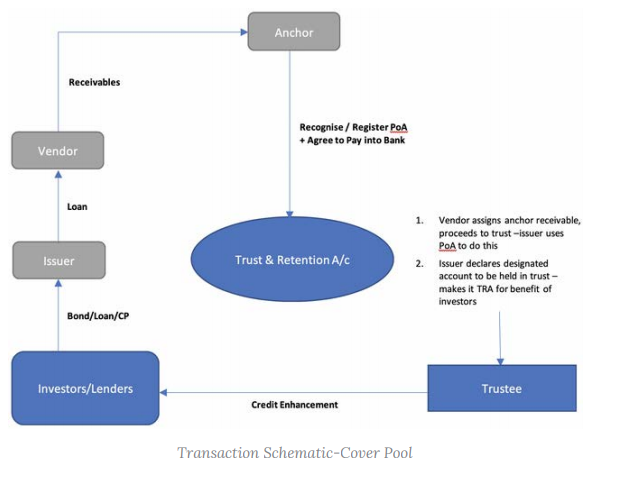

Cover Pool

The issuer asked all the vendors to earmark and pool their anchor receivables into a trust. Since the anchor was rated ‘AAA’, so was the pool. The issuer then arranged for the trust to guarantee the commercial paper. Further, as the receivables matured, they were paid into a trust account so as to be bankruptcy remote from the issuer. Cash was released to the issuer so long as new receivables from the pool of vendors were financed and put into the trust. In effect, a one-year instrument carrying the credit characteristics of the pool was created and used to fund assets with a tenor of 90 days. In short, supply chain had entered the capital and money markets. The structure neatly avoided the questions regarding Reserve Bank of India (RBI) restrictions that usually revolve around securitisations. If the loans were sold into a securitisation trust, what would become of them when they matured? Would they be reinstated? These concerns, however, were not relevant in this case, since there was no securitisation involved. But it did call for a lot of ingenuity in tracking cash flows and ensuring cash flows were released only when new assets were put into the cover pool. Now why can this not be done in the normal manner by creating a charge on the receivables? India’s insolvency law has to be triggered to invoke a floating charge before the creditors take their charged assets and stand in queue. Timing around enforcement and the whole legal process force rating agencies to pause when giving weight to security. In effect, all one gets is the standalone rating of the issuer. In a covered bond, the receivables assigned to the trust are, strictly speaking, the property of the vendors. Other lenders to the issuer have no direct claim on the pool. In case the issuer purchases the receivables and sells them into a trust, its other creditors would relinquish their claim on the receivables only if they receive cash.

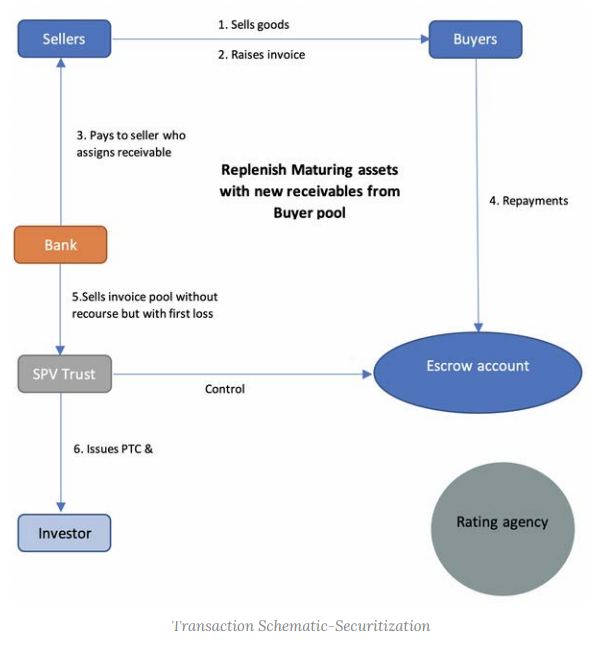

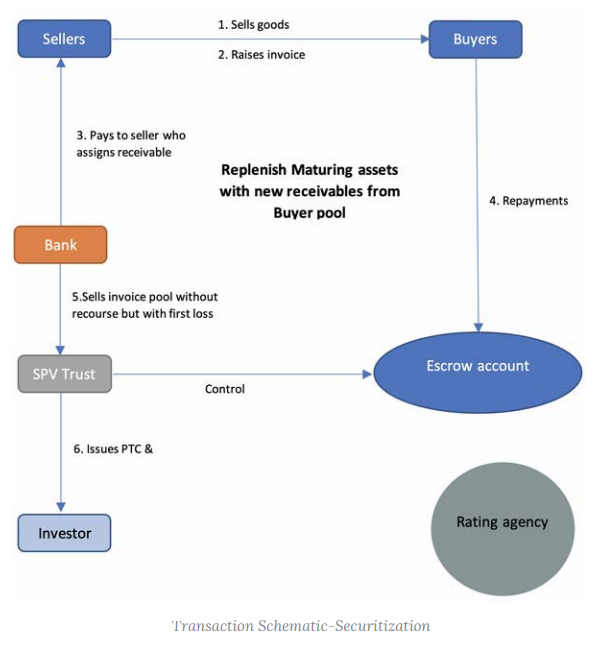

The Securitisation Option

Could the pool have been securitised? From an economic point of view, yes, it made sense to do so. The exposures would be shown as something other than NBFC exposure, and that alone would have been a very welcome outcome. Regulations, however, are not as clear. Typically, the RBI expects originators to hold assets for three months; but what would you do if your asset has a life of only 90 days? Plus there is a very specific prohibition about revolving facilities. Both these restrictions do not apply to companies, which are entities outside the purview of RBI’s supervision. So could a company arrange to securitise the receivables of its suppliers and dealers? Yes, it can and many, in fact, are already working on those lines. These structures hinge on the new fintech capabilities to track repayments and ‘replenish’ the pool of assets owned by the trust as the old receivables mature. Even in the case of banks and NBFCs regulated by the RBI, an old footnote in the guidelines allows trade receivables to be sold without a holding period. The proposed new RBI guidelines allowing ‘replenishment’ structures and moving the proviso on minimum holding period around receivable from a footnote to the main body should also help improve the possibilities for the banks and NBFC providers of supply chain finance. The fact is the trust is now no longer a completely passive entity—it is acting as per its mandate and picking up new assets that are pre approved. Any potential lacunae along questions of—‘is the trust doing business and, therefore, is it taxable?’ are covered by the tax notification that as long as RBI or Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) regulations are followed, it is tax neutral. Given the evolving nature of RBI guidelines just yet, it may be prudent to list all securitised instruments under SEBI guidelines in the near term.

Conclusion

As an asset class, banks and NBFCs have been working with supply chain finance for over 20 years. They see it as a reliable and stable, as well as relatively low risk asset. Currently, the bank market is largely focused on the suppliers and dealers of ‘AA’ or higher rated corporates; but even among them, the product favours larger players and focusses on the top 30% of suppliers and dealers. Capital markets though prize granularity. The more diversified and numerous the borrowers, the better. Further, they can allow the burden of KYC and credit assessment to fall on fintech solutions. As an asset class, if the top 500 companies could help banks build a portfolio of INR 25 trillion, what could the next 5,000 companies build up?