Covered Debt Instruments

Covered Debt Instruments

“It’s only a paper moon and a cardboard sea, But it won’t be make-believe if you believe in me” - Tennessee Williams in A Street Car named Desire.

“Modern capital markets financing is increasingly an act of faith. We rely on ratings, on the words of economists and pundits who quite often live in worlds completely disconnected with reality”. I believed I had cause for a rant… I had an argument with my bank’s portfolio manager. How much return was acceptable for a cash-backed loan that my client wanted? He expounded the LAW to me: Return requirements depend on ratings. [fair enough]. Ratings depend on the probability of default. [with you so far] and The Probability of default has nothing to do with the cash collateral. [huh!]. “It is 101 of banking – what’s your first way out? Cash flows? This is a weak company. So, there is a good chance they will default.” [True enough. But what about the cash?]. “We will give it credit under FSV – Forced Sale Value of collateral @ 95%…” and that was my own little Siddhartha moment… not the moment of startling clarity under the Bodhi tree… rather the moment when he walked out of the house in search of an answer to old age death and disease Banking lives in a complex world of formulae. Capital adequacy. Risk weight and Forced Sales Value for different types of collateral. It is gotten to the point where if your rating is below a certain investment grade, it does not matter what the causes are or what case you build. Financing costs will tend to be unviable. A cash-backed bond will not be AAA. True, these situations are rare. But a bond backed by AAA-rated collaterals? What about a bond backed by a pool of Commercial vehicle loans which if they had been securitized would have been AAA? What about loans backed by receivables of AAA-rated companies? What about a 2x cover on receivables of AA-rated companies?

Floating in the wind

In India security is created in favor of the lender and registered with the Registrar of Companies. In theory this is how it is done everywhere in the world. But what is the process of accessing this collateral? This is usually a big black box. If it is a pledge, (usual for financial instruments), no permission is needed – the lender can sell the collateral. If it is a fixed charge, you need to enforce but cash flows and title cannot change hands without the lenders consent. But in India, the commonest form of charge is a floating charge. This means that the collateral can be sold or changed in the usual course of business – which means that by the time you figure out you need to access the collateral, the first default has probably happened. So yes. It looks like there are solid reasons why security quality should be separated from the quality of the borrower. In a strong enforcement framework the arbitrage or cost of having high-quality collateral for a loan or bond versus a high-quality borrower would not be much. But in India? PMC bank depositors who are covered by Deposit insurance are yet to receive their fully insured deposits. Lenders to DHFL found that some of their assets said to be charged to them had in fact been securitized. Security enforcement is a mess. If one is lending to an NBFC, there is no clearly laid out path to taking them to a bankruptcy court and realizing one’s collateral. (Until the DHFL default caused the government to include NBFCs under IBC.)

Alienating the collateral assets

A lot of the issues relating to security enforcement have actually been tackled by the Indian market through another instrument. This is the market for securitised instruments. At issuances of over INR 10 Trillion per annum this category of debt seems to have addressed many of the same concerns and considerations relating to security. Instead of a debt issuer, the fund raiser is designated as the Originator. Recourse to the originator does not extend beyond the pool of identified loans and yet AAA ratings are possible here. The reason is that the identified pool is placed in a trust which is outside the balance sheet of the fund raiser. Enforcement of the underlying assets is a lot less difficult since the Trust owns the assets for the benefit of investors. Lenders to the Originator cannot claim those assets. Further the investors (through the trust) paid for those assets and deposited the cash with the banker of the Originator – so the lenders lost nothing.

Securitised paper has now been issued in India for over 20 years. So why do lenders not adopt the same structure? Put the collateral in trust and so on? In fact, SEBI requires secured bonds to have a security trustee which will hold the collateral. So, the alienation of the collateral to a trust is done. So why does this structure not get the benefit of the collateral? The short answer is that Indian law does not distinguish between collateral placed with a trustee or directly with the lender. It is all registered with the Registrar of Companies and the level of detail in identifying the collateral is usually up to the lender and borrower. – Usually it is very loosely defined as a charge over all assets. The process of enforcement could take months or more commonly years. By definition, an AAArated asset should have an overwhelming probability that it should get paid on the due date and hence building in the uncertainties of a security enforcement will defeat most structures that seek to use the value of collateral.

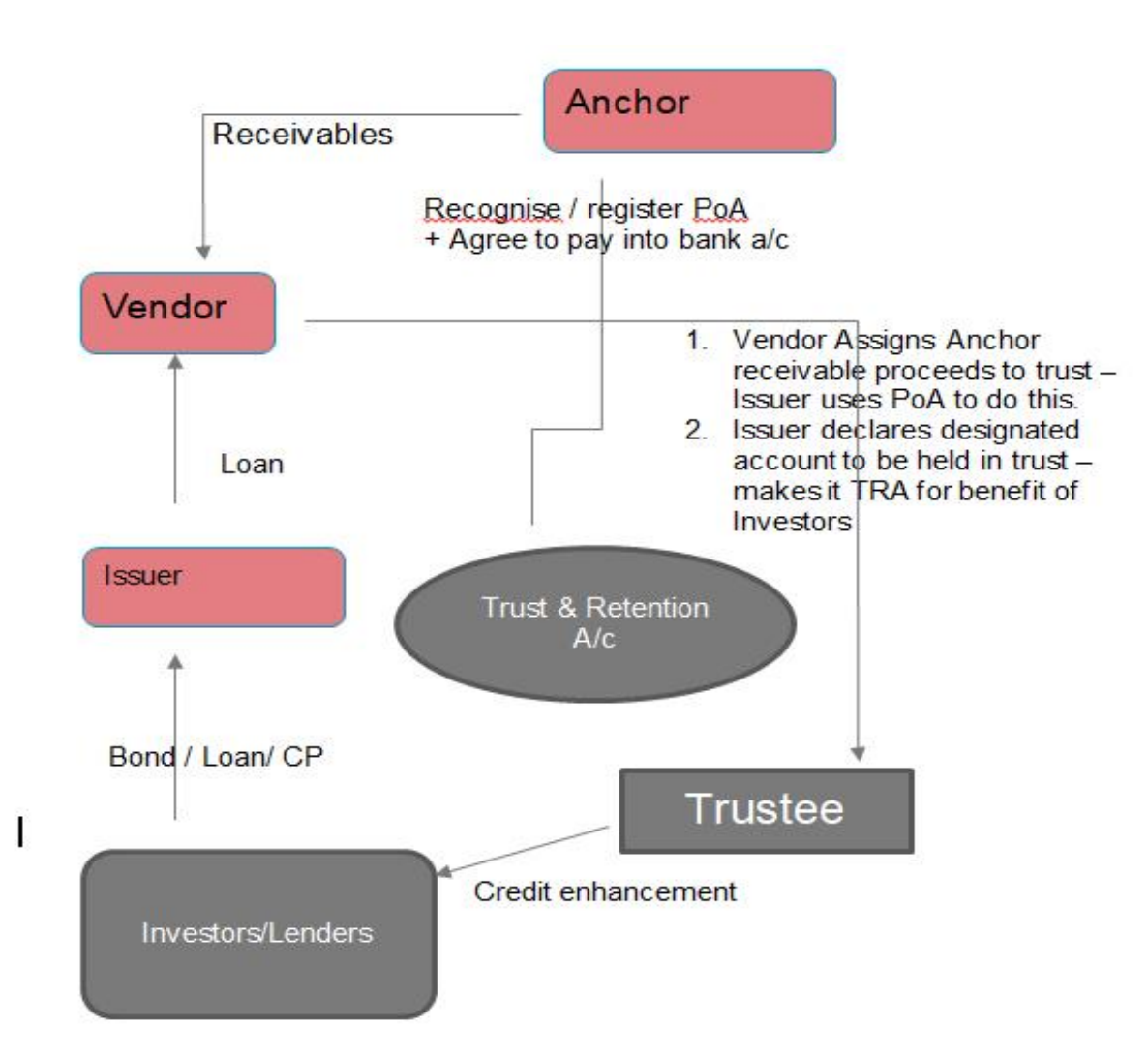

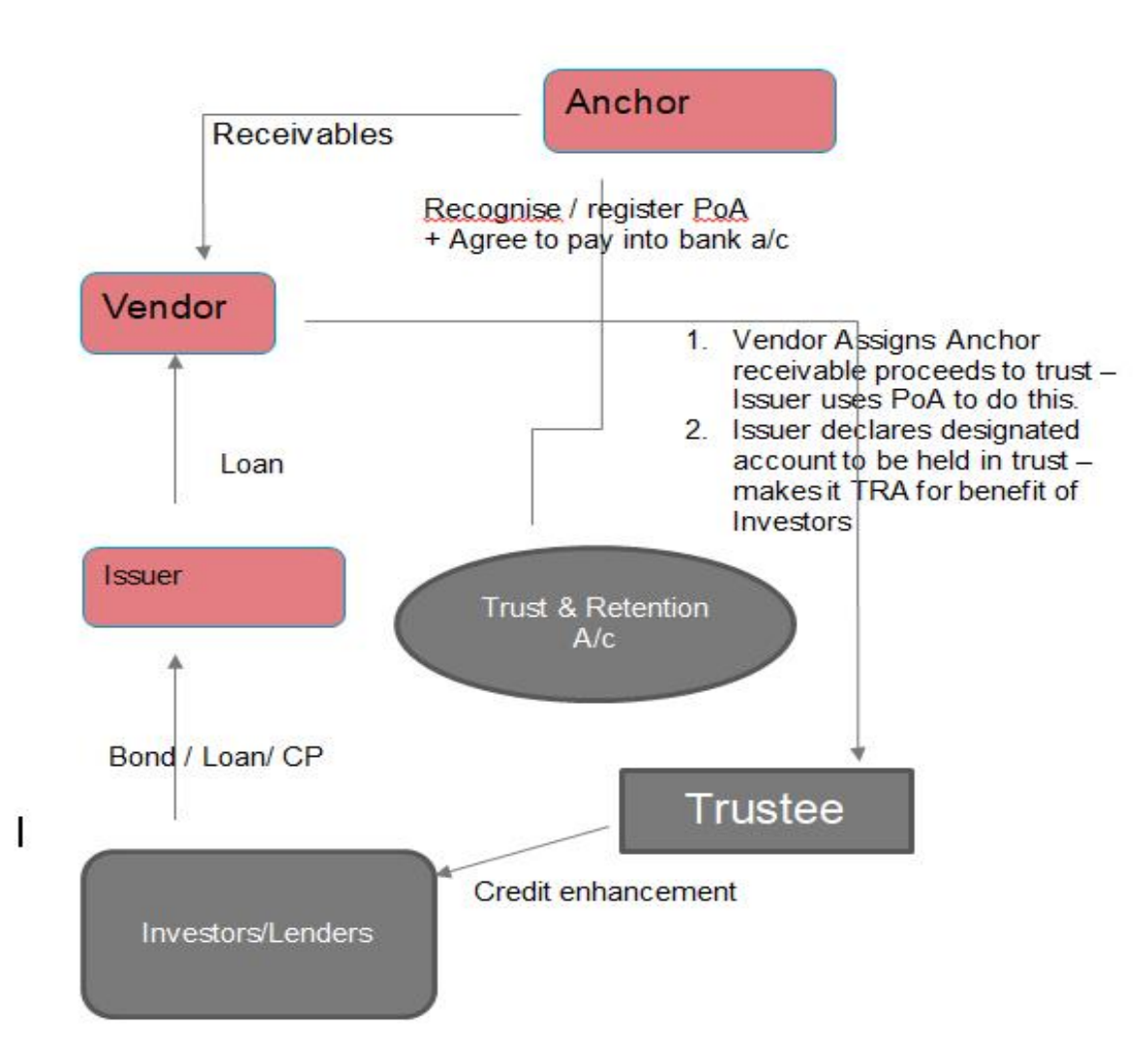

Covered Debt

Rating agencies and lenders have a healthy respect for third party guarantees or third-party credit enhancements. If the third-party guaranteeing a bond is AAA-rated, then so is the Bond. However, there will be a small tag of [SO] to differentiate such offerings. So, could one put the collateral into the hands of a third party who then guarantees the debt offering? Maybe put it into a trust and have the trustee issue a guarantee to the extent of the trust property? In the summer of 2018, a fledgling NBFC sought to buy a supply chain business. Typically the suppliers would provide a 90 day credit period to the buyer and the NBFC in turn, would bridge the cash flow gap by providing a loan to the supplier for 90 days (provided the Anchor had confirmed quantity and quality of goods and waived set off rights). As in all such arrangements, the Anchor provided a measure of operational comfort by agreeing to pay the sums due to the suppliers into the account designated by the NBFC. At the heart of it was a portfolio of loans to suppliers, which would be retired from payments due from an AAArated engineering major. How could a small NBFC with high-cost borrowings fund this high quality but low yielding book? When the book was purchased, documentation was rejigged to allow the borrowers (suppliers) to place their highquality receivables in a trust. The trust then directly guaranteed lenders to the NBFC. The debt was “covered” by direct recourse to cash flows from a high-quality pool. This approach has the advantage that the asset/collateral is no longer in the hands of the borrower. So other lenders to the Borrower could not object. Further, if the Borrower defaulted, the cash flows from the assets held in trust would go directly to the Lenders and repay them. The legal separation of the high-quality collateral from the borrower allowed rating agencies to rate this A1+, the highest short-term rating. It is not a securitisation – recourse to the borrower is fully in place.

But it behaves like one – the underlying pool also need not be static. It can change, but with the consent of the trustee. The cash flows coming from the Anchor were routed into a debt service account owned by a trust set up for the benefit of the Lender to the Covered debt; i.e., any money lying there would be first used to retire the debt obligations of the Lenders and any surplus would be used to pay remaining obligations to the NBFC and if anything is still left over it would go to the vendor This addressed the risk of co-mingling of cash flows from the Cover pool and separated the ownership and title in practice. A court would be unlikely to freeze payments coming into an account which was not in the name of the NBFC.

What did the Structure achieve

The Issuer raised commercial paper which were rated A1+(SO) while the stand alone rating was A2.This impacted cost as well as the universe of investors who would lend to the NBFC Secondly the pool could change daily and the average life of the pool at any point in time was 45 days. However, the instrument had a maturity of 1 year. So, it helped access to term finance. Could securitization of the pool have achieved the same result? Possibly. But some questions would have remained. Can the pool composition change? Would cash flows from the pool be used to buy new receivables? [Is that a replenishment or would it trigger RBI caveats around revolving securitization. What about the minimum holding period of 90 days before a loan is sold? What about the operational debt nature of vendor receivables? And so on.]

Inversion of priorities

A second approach to achieving a covered bond rating enhancement was attempted as well. In this case the NBFC had a portfolio of commercial vehicle loans. A pool of such loans was sold into a bankruptcy remote trust and a third-party investor subscribed to the trust corpus. Since the cash consideration was paid the pool was bankruptcy remote. When the pool’s cash flows were tranched the senior tranche would have qualified for a rating of AA. The investor in the senior tranche however agreed that these cash flows would be used to credit enhance a bond issuance of the NBFC. This inversion of cash flow priority allowed the bonds to be rated AA. Why such a complex structure? Why not place the cash from the sale of loans into a deposit and credit enhance the bond? The answer takes us back to the beginning. Enforcement of collateral is complex in India. Even if it is cash.

Structure rated by ICRA and CARE. Legal advice by Juris Corp and Jerome Merchant Partners.

Conclusion

Indian debt markets have been reeling under the impact of defaults by many large financial institutions. As the environment turns bleak investors have been looking to secure their interests by piercing the veil and looking straight through into the underlying assets to which NBFC and corporates have exposures. A useful statistic to remember is that while the default rates (NPA %) for MSME has consistently hovered at around 12%, it does mean that a good 85% have not defaulted. Covered bonds with adequate asset cover of say 1.25x ought to be very safe indeed.